It turns out that there is. We (Jeffrey Mark Paull and Jeffrey Briskman) recently published an article that looks at the issue of how Jews obtained their surnames in the Russian Empire. As part of the research for that article, we discovered a unique aspect of the Jewish surnaming process that accounts for the myriad number of unique Jewish surnames, and why many members of related families in the Russian Empire often obtained different surnames

Brief History of Jewish Surname Adoption in the Russian Empire

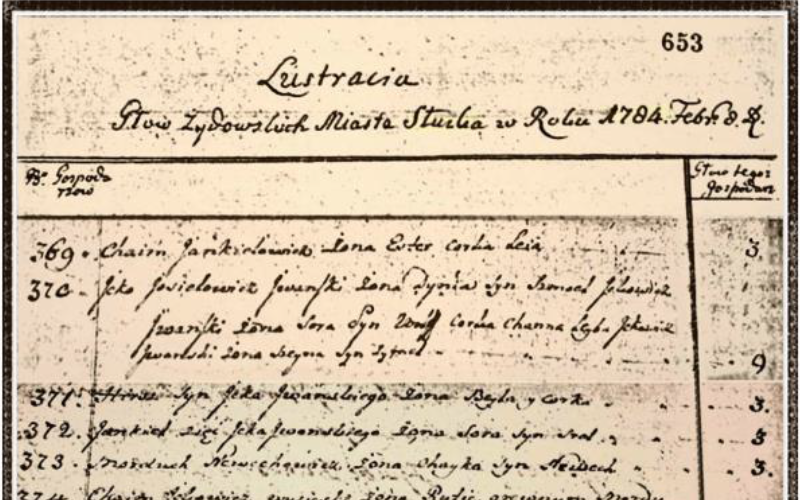

To better understand the Jewish surname process, as it took place in the Russian Empire, a bit of history is in order. With the exception of prominent rabbis, affluent Jewish merchants, and the Sephardim, most Jews did not acquire surnames in Eastern Europe until the Napoleonic era of the late 18th-early 19th century. Due to the need to streamline tax collection and military recruitment procedures, Austria-Hungary (1787), the German states (1790), and the Russian Empire (1804) passed laws that obliged the Jewish population of these countries to adopt hereditary surnames.

As a result of the Partition of Poland by these countries, which was home to more than 90% of all Ashkenazi Jews, the vast majority of modern Ashkenazi Jewish surnames date back precisely to this period. After the final Partition of Poland in 1795, and the Congress of Vienna, the Russian Empire acquired over two million Jews who did not use surnames. Shortly thereafter, Czar Alexander I’s edict of 1804 required all Jews living in the Pale of Settlement (the territory where Jews were permitted to live in the Russian Empire, encompassing modern Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova) to adopt permanent surnames.

A second edict, issued by Czar Nicholas I in 1835, prevented Jewish surnames from being altered or changed. Pursuant to the 1835 surname law, and after the dissolution of the Kahal (Jewish community councils) in 1844, it was agreed that: “Every Jew, head of the family, is declared by which name and surname he is written in censuses, added into both family and alphabetical lists, and in passports, and other documents”

The manner in which Jews adopted or were assigned surnames took many forms throughout the Russian Empire. Under the czarist edicts, there were many ways in which Jews selected or received their surnames, and different areas and jurisdictions had different rules. However, there is one unique feature of the surname adoption process that helps explain why we see so many different Jewish surnames today, even among closelyrelated paternal lines, and that was the tendency for the heads of households to adopt unique surnames.

The direct result of the Czars’ surname edicts and the ensuing Russian laws and regulations, was the adoption of different surnames by members of the same family, if they happened to live in different households, resulting in the creation of numerous subdivided family units of interrelated people having different surnames.

It is not known with certainty if the requirement that all heads of households adopt unique surnames was uniformly enforced by the Russian authorities, or whether unique surnames were sometimes voluntarily adopted in an effort to avoid the harsh taxation and military conscription policies that were imposed on the Jews living in the Pale of Settlement. Most likely, it was a combination of both factors that resulted in the widespread adoption or assignment of unique surnames for families living in different households.

Prior to 1827, according to a ruling by Czarina Katherine the Great, the Jewish community was not summoned to the army; instead they had to pay double tax. Taxes were based on the number of males in the household, which would have created a powerful incentive to divide families into smaller units by adopting different surnames. After 1827, according to a law issued by Czar Nicolas I, Jews were liable to conscription.

Being drafted into the Czar’s army was a particularly onerous and menacing proposition for Jews in the Pale, and they tried to avoid the draft by “fiddling around” with their surnames; e.g., having boys registered as belonging to another family which had no sons, hiding sons from the census takers, and doing other things to make it difficult for the Russian authorities to find them. Continue Reading…

Authors