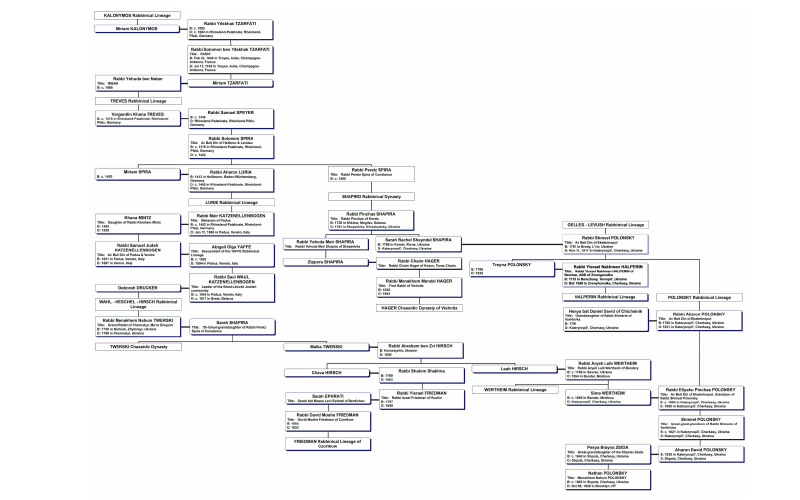

When a paper trail for a rabbinic genealogy exists back before the mass adoption of Jewish surnames, DNA testing can be useful both to confirm relationships and to help identify other living members of the extended family, many of whom have different family surnames and do not know of the rabbinic relationship. Y-DNA testing of members of the Polonsky rabbinic family demonstrates this process.

The present study focuses on a family of Jewish descent that immigrated to America from the Ukraine during the early part of the 20th century. It presents the genealogical and genetic data that characterizes the Polonsky rabbinical lineage by which its descendants may be identified. The Polonsky rabbinical lineage descends from a nexus of great Talmudic scholars, Jewish community leaders and rabbinic dynasties that formed the bedrock of Judaism throughout Europe and Russia.

Introduction

Major challenges and difficulties abound in the study of Jewish genealogy. These challenges and difficulties are well known to Jewish genealogists: frequent expulsions and migrations, the dearth of civil and Jewish community records, the lack of Jewish surnames, and the widespread destruction of the repositories of Jewish learning and culture, including synagogues, yeshivas and cemeteries.

As a result, for many people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent, no genealogical records of their ancestors can be found beyond a certain point. Against this reality, however, are a limited number of great rabbinical families whose lines of descent were studied and preserved over the centuries. These families include some who rose to prominence through the great distinction of one or two individuals, and others who produced a succession of illustrious rabbinical scholars or community leaders.

A wealth of genealogical information exists in the Jewish literature for individuals who can establish descent from one or more of the great rabbinic families. Rabbinic sources can provide priceless information regarding their descent to Jews who

Because of the endogamous nature of the Ashkenazi Jewish population, many, if not most Ashkenazi Jews descend from a prominent rabbi or rabbinical lineage, although they may not be aware of it. Endogamy among Ashkenazi Jews was internally mandated through religious and cultural tenets that endorsed marrying other Jews, and was often externally imposed through laws that prohibited marriage to non-Jews.

Culturally, the practice of shidduch, or arranging marriages between family members of equal yichus or distinguished birth, was common among Ashkenazi Jews for centuries. To have yichus was to be descended from illustrious ancestors who were famous rabbis or community leaders.3 Many rabbinical dynasties made it a priority to ensure that their children married into other prominent and often closely related rabbinical lineages, resulting in frequent consanguineous marriage among cousins of these lineages, resulting in the creation of a highly endogamous population.

This high degree of interrelatedness is one reason why increasing numbers of Ashkenazi Jews are turning to genetic testing as a way of recovering part of their lost heritage by locating “DNA cousins” and identifying their common ancestors. As they do, it is becoming increasingly clear that characterizing the unique DNA markers of the great Ashkenazi rabbis and rabbinical lineages will play a critical role in the ultimate success of such endeavors. Studies such as the “WIRTH” project5 and the Wertheimer-Wertheim autosomal DNA study6 have demonstrated the intrinsic value of and need for characterizing rabbinic DNA in an effort to bridge the gap between genetic data and the missing paper trail for Ashkenazi Jews.

Hence, studies such as this, which provide the genealogy of a renowned rabbinical lineage of Ashkenazi descent, combined with the genetic data that describe the unique DNA markers or characteristics of that lineage, have considerable value for both present and future Jewish genealogical studies. Such studies provide the unique autosomal or Y-DNA markers—the generic fingerprint of a specific rabbinical lineage, the gold standard by which individual DNA test results can be compared to determine if a given individual may be a descendant of a particular rabbi or rabbinical lineage

Background

The three million Ashkenazi Jews who immigrated to America from Russia between 1881 and 1920 wanted to break with their past and make a new life for themselves

Such was the case for the Polonsky family.

Menakhem Nahum Polonsky, with his wife and four of their children, left Cherkasy, Russia, and settled in Brooklyn, New York, in 1914. Upon his arrival, Menakhem Nahum Americanized his name to Nathan Polonsky and reunited with his other four children who had previously immigrated to the U.S. Among their descendants, little was known about their life before America. Other than whisperings of the family being somehow descended from one of the disciples of the Baal Shem Tov, the founder of Hasidic Jewry, there was no family tree or paper trail to document their ancestors.